As an expansion on our cathedral-vision of education, I offer this interpretation of Milton Gregory’s “Seven Laws of Teaching,” an excellent set of principles for classical Christian educators to follow, whether at home or in the classroom.

-

“A teacher must be one who knows the lesson or truth to be taught.”

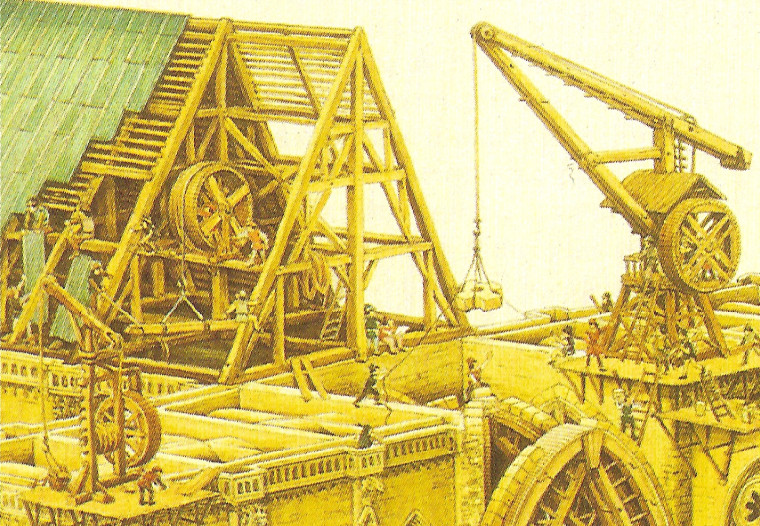

The builders of cathedrals, the ones who do the work, can be sorted into two categories – unskilled laborers, and master craftsmen. The master craftsmen are the ones who know their craft inside and out – carpentry, sculpting, blacksmithing, roofing, glass making, stone cutting, masonry, etc. Each master craftsman is responsible for making sure that his portion of the cathedral is constructed correctly and with excellence. In order to do that, he has to know what he’s doing! He is someone who has already been through an apprenticeship in the craft and who has a great store of experience and knowledge to bring to bear. But he also keeps his skills sharp by exercising his craft himself, not just directing others how to do it. He has to be organized, and he has to show up to each day of work prepared for the tasks that need to be completed.

Educators likewise have to come to our lessons prepared, having studied and reviewed the material ourselves so that we can accurately and thoroughly teach the material. As Gregory puts it: “Know thoroughly and familiarly the lesson you wish to teach; or, in other words, teach from a full mind and a clear understanding.”

-

“A learner is one who attends with interest to the lesson given.”

If you’ve ever been inside a cathedral, you know how captivating it is. Many cathedrals are tourist destinations because of the beauty the offer and the interest they hold. That’s what we want our lessons to be like for our students! To some extent this one is on the students – they have to be one ones attending. We can’t attend for them. But we can facilitate attention. We do this firstly by making our lessons worthy of attention. As a cathedral demands our interest because of its beauty, its sheer size, its symbolism, and the awe which it inspires, so our lessons should garner students’ attention by making truth beautiful and by engendering wonder. We do it secondly by attending ourselves to the inattention of our students. We must insist on students’ attention when distraction inevitably strikes. In Gregory’s words: “Gain and keep the attention and interest of the pupils upon the lesson. Refuse to teach without attention.”

-

The language used as a medium between teacher and learner must be common to both.

This law seems like it should be obvious, and to some extent it is, but it’s one that we need to be mindful of. We know that a common language is needed for construction from the Tower of Babel story. When God disrupted the people’s ability to speak the same language to each other, their ability to continue construction together came to a screeching halt. If we’re going to build an education with our students, we have to use their language.

But just because we’re all speaking English (or Latin or Spanish) does not necessarily mean we’re speaking a common language. We have to be sensitive to the fact that our students don’t necessarily share our depth of vocabulary, or have a grasp on the vocabulary used in a particular field, so we have to use what they know. Gregory expands upon Law 3 in this way: “Use words understood by both teacher and pupil in the same sense – language clear and vivid alike to both.” That doesn’t mean we can’t teach new vocabulary, but we do have to use words which our students do know to teach that new vocabulary. That, incidentally, is Law 4.

-

The lesson to be learned must be explicable in the terms of truth already known by the learner – the unknown must be explained by the known.

It would be ridiculous to try and build a cathedral, or any building for that matter, from the top down. Everyone knows you first have to build a foundation, and then gradually build up from that foundation. We can think of the foundation of learning as the truths already known by the learner. We have to first consider what kind of foundation the student has, and then use that foundation to support and uphold the next piece. On this law Gregory writes, “Begin with what is already well known to the pupil in the lesson or upon the subject, and proceed to the unknown by single, easy, and natural steps, letting the known explain the unknown.”

-

Teaching is arousing and using the pupil’s mind to form in it a desired conception or thought.

If you walked into a cathedral as a modern-day tourist and your tour-guide mechanically explained all its parts to you, you would probably gain a basic understanding of the cathedral, but you probably would not be inspired to truly marvel at the cathedral or to love it enough to explore more of it. If, on the other hand, the tour guide were to point out areas where you should direct your attention and ask you to consider why they might be designed the way they are, if he directed your powers of attention and logic so that the significance of the structures dawned on you in your own mind, the experience would be much more formative and would probably last much longer in your memory. As curators of the Great Tradition, classical educators must “Use the pupil’s own mind, exciting his self-activities. Keep his thoughts as much as possible ahead of your expression, making him a discoverer of truth.” Socratic and mimetic teaching especially help us do this.

-

Learning is thinking into one’s own understanding a new idea or truth.

In order to build the flying buttresses that support the walls of a cathedral, workers have to create temporary wooden frames that hold the structures in place until the real stone arches of the buttresses are completed and hoisted up into position. Those structures, called centerings, are required for the building process, but the goal is always that the structure would be able to stand on its own eventually.

Likewise, in education, Gregory says we must “Require the pupil to reproduce in thought the lesson he is learning – thinking it out in its parts, proofs, connections, and applications till he can express it in his own language.” When we ask our students to do this, it’s like removing the wooden centering and asking the student to hoist up the permanent, stone arch and fix it into place. If a student can express the idea or truth in her own language, then she can stand on her own with that idea or truth.

-

The test and proof of teaching done – the finishing and fastening process – must be a reviewing, rethinking, re-knowing, and reproducing of the knowledge taught.

Nowadays if we visit a cathedral, it’s usually just for a one-time tourist visit. But that’s not what cathedrals are really designed for! All of what one learns through progressing through a cathedral and the parts of a service held in it are supposed to be repeated again and again. That repetition solidifies the knowledge gained until it becomes deeply ingrained in an individual.

The same holds true in education. We must review and repeat the knowledge and skills that we want our students to hold on to until they are so deeply embedded in our students that they can reproduce it without our guidance. As Gregory puts it, “Review, review, review, reproducing correctly the old, deepening its impression with new thought, correcting false views, and completing the true.”